Wiley brings ‘Blood’ to Thalian

Posted by MikeWileyProductions in Review / News on January 9, 2011

By Bob Workmon

StarNews Correspondent

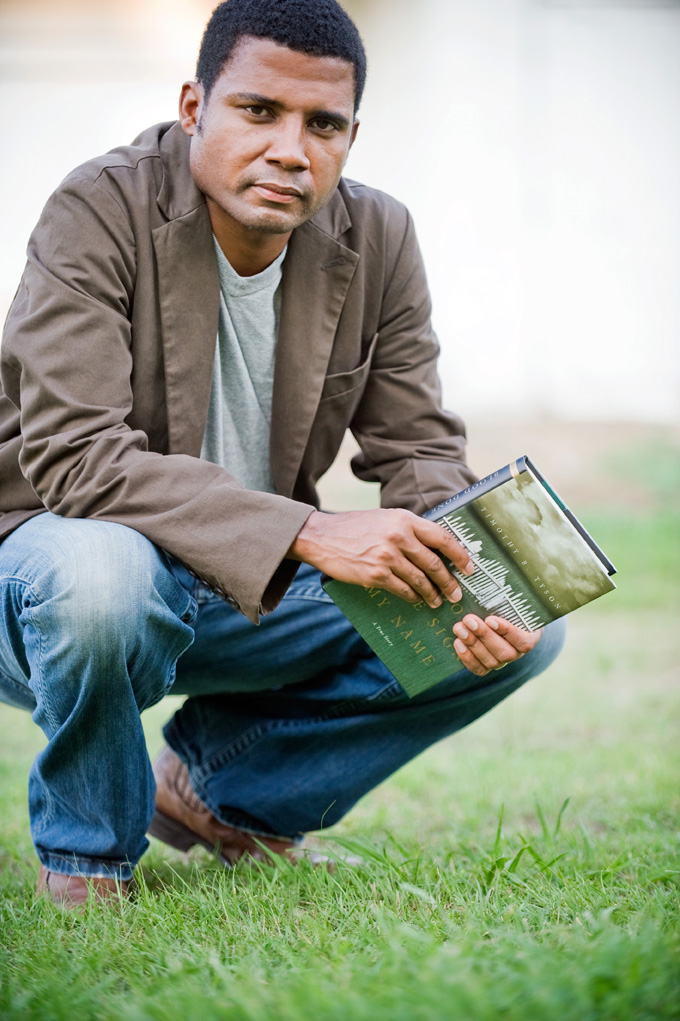

Mike Wiley got his master’s degree in theater from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 2004. It was the same year that “Blood Done Sign My Name,” Tim Tyson’s searing examination of the events that led to the 1970 murder of Henry “Dickie” Marrow in Oxford, N.C., was published.

Though they would not meet for another two years, Wily and Tyson were on a course that made the collaboration inevitable, the fruits of which Wiley will display at Thalian Hall on Saturday night.

Wiley, 38, is a versatile actor, playwright and an accomplished practitioner of something called documentary theater. (Think “The Laramie Project.”) It was seeing Wiley’s performance of one such play in 2006, “Dar He: The Life of Emmett Till,” another true and tragic story of racial hatred and murder, that inspired Tyson to suggest a stage adaptation of his book.

“I hadn’t read Tim’s book at that point,” Wiley said.

But soon he was pouring over Tyson’s notes and recorded interviews with Oxford residents, black and white. He also conducted his own research.

“Documentary theater can be as literal as court transcripts,” Wiley said by phone last week from Alabama, where he was working with students at Troy State University, as well as performing. “What I do through interviews, diaries (and) newspaper articles is take direct sources into a play. It comes closer to what the truth is by searching for an ultimate truth using their words.”

Wiley said that a theatrical approach to histories like that of Oxford does something extraordinary by representing all of the people involved in one place – on stage – depicting the facts with precision and taking care to acknowledge nuances that may excite prejudices.

“As Tim Tyson in the play, I float through, asking these people the questions,” Wiley said. In all, he plays about 40 characters in “Blood Done Sign My Name.”

Mike Wiley

In light of recent discussions around the new, revised edition of Mark Twain’s novel “Huckleberry Finn,” it’s interesting to note the use of the word “nigger” in the play, as well as in Tyson’s book.

“It was the weapon of choice,” Wiley said of the word, whether in the late 20th century or Twain’s time. “In all my work I use multiple perspectives to educate, and the use of certain language is part of that looking with clear vision at our history. Whitewashing the use of that word robs us of the opportunity to know ourselves and learn from it.”

Certain questions can arise when audiences react to Wiley’s work, questions such as, “Why is this still relevant?” and, “When are we going put this to rest?”

“A number of responses come to mind,” Wiley said. “First, many people are unwilling to look at the role they or their family played, unable to accept the darker side that sometimes goes hand in hand with otherwise proud histories.

“Parents and school teachers duck the subject, thinking that if you don’t teach it, it never happened,” he continued. “But if we don’t teach it, we stand a much greater chance of repeating it with more tragic consequences. That why we’ve got to talk about it. We’ve got to get to know our neighbors.”

And Wiley means that metaphorically as well as literally.

Tyson and gospel recording artist Mary D. Williams will appear with Wiley for the Thalian Hall performance on Saturday. They will also lead a panel discussion on the UNCW campus from 11 a.m.-noon Saturday in Leutze Hall, room 108. The discussion is free and open to the public, but seating is limited. More information is available and reservations can be made by e-mailing artsinaction@uncw.edu.

“Blood Done Sign My Name” was a catalyst for change in Oxford, Wiley said. It was Tyson’s personal search for answers about the meaning of truth and justice, as well as a way to examine his relationship with his father, a respected Presbyterian minister who became a villain to blacks and whites after attempting to bring peace to a community engulfed in anger and pain. Wiley visited Oxford to do research and, later, performed the show there.

“It’s not tied up with a bow,” he said. “But at least people talk to one another.”

Leave a comment